The European Commission launched a public consultation on its proposed Skills Portability Initiative (SPI), a measure intended to reduce barriers to the recognition of skills and qualifications across the European Union. According to Europass, SPI aims to improve how people’s skills and qualifications are used and accepted across EU Member States and, therefore, support worker mobility, address labor shortages, and boost competitiveness in the EU.

SPI is a comprehensive package of three interrelated actions.

“Action 1: a potential legislative proposal to facilitate worker mobility through improved transparency of skills and qualifications, and digitalisation.

Action 2: potential measures to facilitate, modernise and expand recognition processes for regulated professions. (Directive 2005/36/EC)

Action 3: a potential legislative proposal for common rules to simplify procedures for the recognition of qualifications and skills of third-country nationals.

The package is included in the Commission Work Program for 2026 (planned for adoption in Q3 of 2026) as part of the EU Fair Labor Mobility Package.“

Participation is welcome! The call for evidence and feedback is open from December 5th, 2025, through February 27th, 2026 (midnight Brussels time). The Commission would like to hear your views. This call for evidence is open for feedback. Your input will be taken into account as we further develop and fine-tune this initiative. Feedback received will be published on this site and, therefore, must adhere to the feedback rules.

Europe’s Competitiveness Gap

The urgency of skills reform is amplified by Europe’s declining competitive position. As McKinsey Global Institute (2024) observes:

“Alongside its divergence in productivity growth relative to the United States, Europe’s competitiveness is also waning. The issues appear to be systemic rather than cyclical. European companies lag behind US peers on multiple key metrics, such as return on invested capital, revenue growth, capital expenditure, and R&D” (p. 6).

This competitiveness gap reflects deeper structural challenges. McKinsey’s research indicates that Europe lags in eight of ten key cross-sector technologies, where “winner takes most” effects are common, with European companies maintaining an edge only in cleantech and next-generation materials (McKinsey Global Institute, 2024). These technology adoption delays, dating back to the 1990s information and communications technology revolution, underscore why initiatives like SPI are critical for Europe’s economic future.

The Skills Transformation Imperative

The scale of workforce transformation required makes skills portability essential. According to McKinsey Global Institute (2024):

“By 2030, Europe could require up to 12 million occupational transitions, double the prepandemic pace. In the United States, required transitions could reach almost 12 million, in line with the prepandemic norm. Both regions navigated even higher levels of labor market shifts at the height of the COVID-19 period, suggesting that they can handle this scale of future job transitions” (p. 3).

This massive shift in labor demand, driven by AI and automation adoption, transforms skills portability from an administrative concern into an economic necessity. The report notes that up to 30 percent of current hours worked could be automated by 2030 in a midpoint adoption scenario, with demand rising for STEM-related, healthcare, and other high-skill professions while declining for office workers, production workers, and customer service representatives (McKinsey Global Institute, 2024).

Building Digital Commons for Skills Recognition

The Commission’s open source strategy aims to address infrastructure gaps that could undermine skills initiatives. The forthcoming strategy will complement the Cloud and AI Development Act and build on successful EU initiatives, including the Next Generation Internet program and the recently launched Digital Commons European Digital Infrastructure Consortium (EDIC) (European Commission, 2026). These infrastructure investments are essential for creating the digital backbone needed to support portable, verifiable credentials across member states.

Europe’s Policy Baseline

Within the EU, SPI builds on existing instruments such as the European Qualifications Framework and the recognition regime for regulated professions established under EU law. These frameworks already support transparency and comparability, but they operate largely as parallel systems. The proposed initiative seeks to integrate them more closely, combining digital credential tools, streamlined recognition procedures, and reforms to professional regulation.

What distinguishes SPI from earlier efforts is its ambition to consolidate these elements into a single policy architecture that could be anchored in legislation. Internationally, skills recognition initiatives tend to rely on voluntary coordination or sector-specific arrangements. By contrast, the EU approach reflects the logic of the single market, where labor mobility is treated as a foundational economic principle rather than an optional outcome.

Consequences for US Higher Education

From an education policy analysis perspective, SPI is likely to have several consequences for United States education institutions, particularly those engaged in internationalization, credentialing, and workforce alignment. By integrating instruments such as Europass and the European Qualifications Framework into a single legislative architecture, the European Union is moving toward a more legible and interoperable skills ecosystem, which highlights structural differences with the U.S. system, where credentials remain fragmented across accrediting bodies, state licensure regimes, and institutional practices. As European credentials become more transparent and machine-readable, U.S. institutions may face increased pressure from employers and international partners to provide clearer skills-based documentation rather than relying primarily on degree titles and credit hours.

If SPI lowers friction on labor mobility within Europe, the relative attractiveness of the United States as a study-to-work destination may diminish for students seeking predictable recognition and professional mobility. Professional programs in fields such as teaching, healthcare, engineering, and social work may be particularly affected, since the EU treats skills recognition as an extension of single market integration, while the U.S. approach remains tied to state-level professional regulation. SPI also reframes quality assurance around demonstrated competencies and verified outcomes, potentially creating tension with U.S. accreditation models that emphasize institutional inputs, governance, and mission. At a strategic level, SPI reflects a coordinated alignment between education, labor, and economic policy within the European Union, an alignment that has no direct equivalent in the United States and that may shape future global expectations around credential portability and workforce readiness.

Multilateral Norms: Coordination Without Enforcement

At the multilateral level, organizations such as the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) have long promoted skills comparability and recognition as drivers of mobility and productivity. The OECD’s work on skills strategies and credential transparency focuses on comparability and data, but it lacks binding mechanisms. UNESCO’s Global Convention on the Recognition of Qualifications concerning Higher Education seeks to establish minimum principles for cross-border recognition, particularly beyond Europe. Its strength lies in norm-setting rather than enforcement.

Europe’s SPI differs in that it aims to operationalize these principles inside a single market with legislative reach. In that sense, it represents one of the more advanced attempts to translate global norms into binding regional governance. UNESCO’s Global Convention on the Recognition of Qualifications concerning Higher Education establishes minimum principles for cross-border recognition, particularly beyond Europe. The convention’s influence lies in standard-setting rather than enforcement, as implementation is left to national authorities.

Against this backdrop, SPI represents an effort to translate these global norms into binding regional governance. By operating within a single legal and economic space, the EU aims to move beyond coordination toward operationalization.

The United States: Decentralization and Sectoral Solutions

The United States offers a contrasting model. There is no federal equivalent to SPI, and responsibility for credential recognition is dispersed across states, professional bodies, and sectors. Initiatives such as Credential Engine address credential transparency and data interoperability, supported by federal agencies through competitive grants and workforce programs. These efforts aim to make qualifications more intelligible to employers, but they do not carry regulatory force at the national level.

For regulated professions, interstate licensure compacts serve as mechanisms for occupational mobility, such as in medicine and nursing. While these compacts reduce barriers, they remain profession-specific and depend on state participation. The overall system prioritizes voluntary coordination and incremental reform rather than comprehensive integration. The comparison highlights a key divergence. Where the US relies on decentralized experimentation, the EU is pursuing a more systemic solution aligned with its internal market framework.

Asia-Pacific: Recognition as Competitiveness Policy

In the Asia-Pacific region, skills recognition is often embedded in broader workforce and competitiveness strategies. Australia and New Zealand operate national qualifications frameworks designed to support international comparability, complemented by bilateral and regional recognition agreements. Singapore’s SkillsFuture initiative emphasizes skills transparency and employer recognition, supported by digital records of learning and certification.

These systems share SPI’s underlying premise that skills must be legible beyond the institution or jurisdiction in which they were acquired. What they generally avoid is the cross-national legal harmonisation challenge that the EU faces within its multi-level governance structure.

Why SPI Matters Beyond Europe

Internationally, SPI positions the EU as a testing ground for large-scale reform of skills mobility. Its significance lies less in any single technical instrument than in the attempt to link digital credentials, professional regulation, and third-country recognition within a unified framework. This approach reflects a wider policy trend toward treating skills as economic infrastructure rather than solely as educational outputs.

Whether SPI becomes a reference point for other regions will depend on implementation. Indicators such as recognition timelines, administrative costs, and employer uptake are likely to shape assessments of its effectiveness. If the initiative delivers measurable improvements, it may attract attention beyond Europe. If it remains primarily a coordination exercise, it risks joining a long list of underused frameworks.

What is clear is that the problem SPI addresses is not uniquely European. The consultation takes place at a moment when skills mobility is increasingly understood as a condition for labor market resilience and economic adjustment, rather than a peripheral issue of professional regulation.

AI-driven Automation and Work Boundaries

As AI-driven automation and remote systems expand the boundaries of where work can occur, skills portability is increasingly implicated in domains that, until recently, lay outside labor-market policy altogether. Developments in lunar and asteroid resource extraction, promoted in strategic roadmaps by agencies such as the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and the European Space Agency (ESA), point to future occupations combining robotics, geoscience, systems engineering, and (in the author’s opinion) planetary environmental governance.

In Living and Working Among Machines: NASA Chief Technologist Discusses the Future of Artificial Intelligence in the Workforce, Chief Technologist Douglas Terrier shared at The Washington Post’s Transformers: Artificial Intelligence event on March 20. “There will be jobs that will change and the skill set will change, but there will also be myriad jobs that will be created that don’t exist today. So, I think there’s a lot of opportunity.”

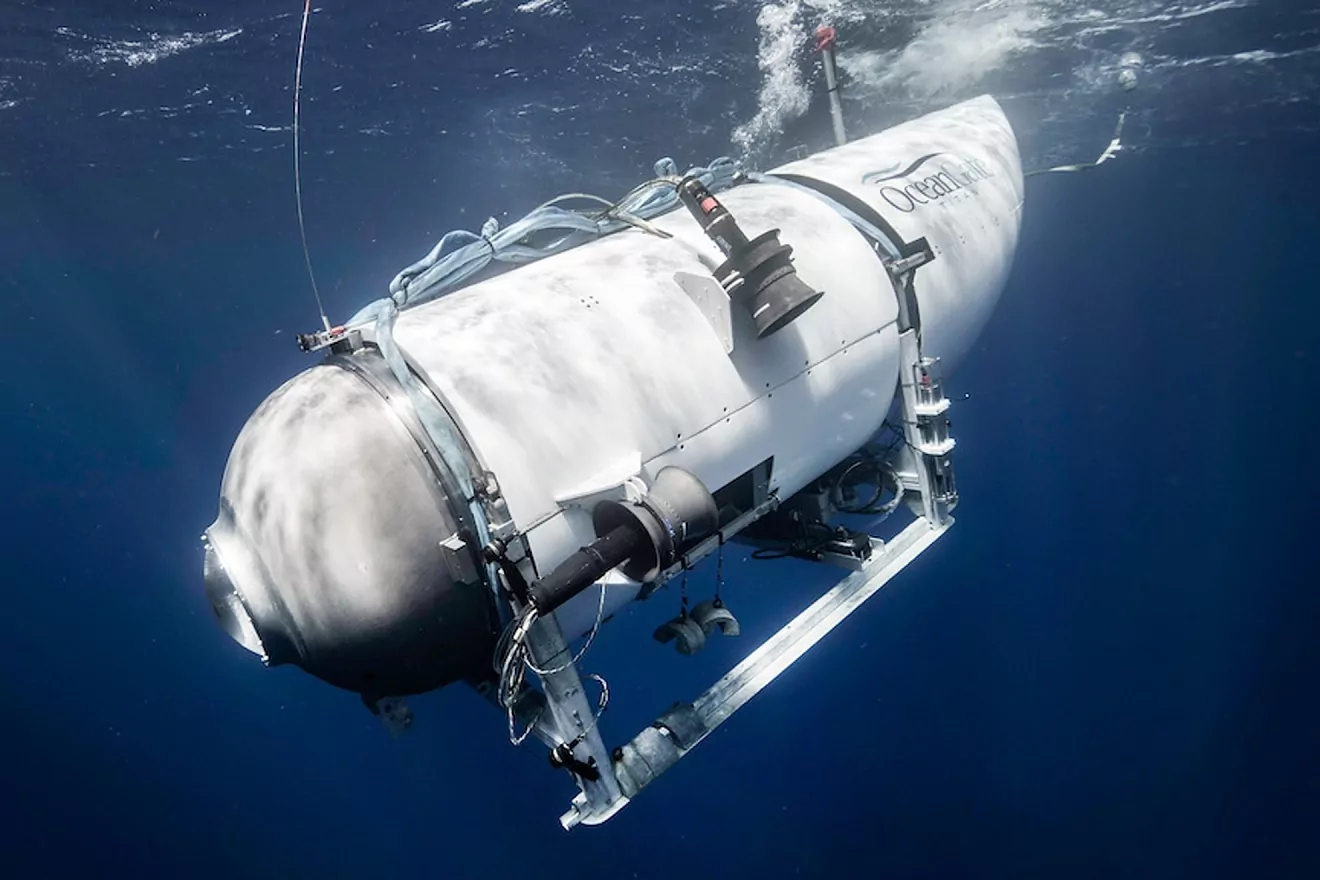

Similar dynamics apply to deep-sea and ultra-hostile environments on Earth, where AI-enabled operations reduce physical presence while increasing reliance on highly specialized, cross-disciplinary skill sets, as in ESA’s initiative. How will space transform the global food system?

These emerging jobs do not align neatly with existing qualification or licensure categories, and they are likely to be internationally distributed by design. In such contexts, the question is no longer how to recognize a profession, but how to verify and transfer composite capabilities across jurisdictions, sectors, and regulatory regimes. Skills portability frameworks such as SPI anticipate this shift, treating labor mobility not as a function of geography alone, but as an institutional response to work that increasingly takes place beyond traditional workplaces and industries, and perhaps, in the future, even beyond planetary boundaries.

McKinsey Global Institute. (2024, May 21). A new future of work: The race to deploy AI and raise skills in Europe and beyond. McKinsey & Company.https://www.mckinsey.com/mgi/our-research/a-new-future-of-work-the-race-to-deploy-ai-and-raise-skills-in-europe-and-beyond

Dr. Jasmin (Bey) Cowin, a columnist for Stankevicius, employs the ethical framework of Nicomachean Ethics to examine how AI and emerging technologies shape human potential. Her analysis explores the risks and opportunities that arise from tech trends, offering personal perspectives on the interplay between innovation and ethical values. Connect with her on LinkedIn.